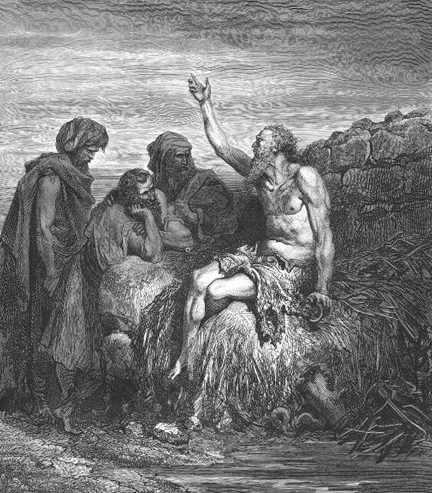

Each of Job’s friends had an elaborately constructed theological explanation for the epic crap storm they had just watched their friend go through. They argued their hypotheses eloquently. The presented them forcefully. But at the end of the book, we find God Almighty lining them up, verbally pulling their pants down, and drawing the word “LOSER” on their foreheads with a Sharpie.

God was apparently insufficiently impressed with their theological arguments.

From then until now, spiritual and/or religious folks have been irresistibly drawn to to making sense of tragedy (Mr. Moth, meet Prof. Flame. Flame . . . this is Moth. You two should get together.)

This is on my mind because it’s been a very tough week for a few people close to me and for about 127 million folks very far away.

Our pastor’s long-time administrative assistant died quite suddenly a few days ago. We’d known Judy for pretty much all of her nine-year tenure as the administrative hub of one of the fastest growing churches in America. In excellent health, she picked up a nasty strain of E.coli in something she ate. This led to a cascade of catastrophic health events that ended in her passing away in less than a week.

At pretty much the same time, a young man at my daughter’s high school, a senior, active in his church and a worship leader in his youth group, died after having spent a couple of months in a deep coma resulting from some sort of aneurysm.

Luke, like Judy, was a good person. Bad stuff happened to them. And as I write, bad stuff on a massive scale continues to happen in Japan.

Tragedy tends to bring out the armchair theologian in many. And I understand why. For one thing, it’s when we’re most likely to hear people impugning God’s character. We hear people uttering questions like “If there is, as you Christians claim, a benevolent God in charge of the universe, how is it that he allows things like this to happen?”

Or we hear others using the opportunity to reject our faith altogether. My daughter tells me several of her fellow students at her Christian school announced this week that they no longer believe in God because of what happened to Luke.

Now we like God. And we have chosen to align ourselves with His cause. And we want others to come over to the cause as well. So when people start talking trash about Him, we tend to rush to His defense.

On top of this is another very human tendency, rooted in our insecurities, to feel personally rejected when someone rejects the thing upon which we’ve built our entire lives.

Our reaction tends to be to rush in and passionately defend our choice by defending God. We can’t resist the urge to become God’s PR agent–explaining him and improving His image.

Of course, this requires addressing thorny theological issues like The Fall, the nature of God’s sovereignty and how it comports with Man’s free will. These are questions with which Christendom’s best minds have been grappling since the first century.

But faced with a doubter or a skeptic pointing to tragedy, few believers can resist rushing in to explain it all in two minutes or less.

Here’s the problem with all that. First of all, God is not insecure. His self-esteem is not fragile. And He’s been handling rejection with grace and patience for quite a long time now. Sometimes, when the doubters and fist shakers get really fierce and fiesty, God finds it amusing (See Psalm 2:1-2).

Furthermore, doubters and pointy-headed skeptics are rarely won over by intellectual arguments (although Paul attempted this at Mars Hill with mixed success.) The Bible makes it pretty clear that our primary weapons of persuasion are these:

Love. And Power.

Our trouble is that the brand of Christianity most of the American church displays right now is somewhat deficient in one or both of these commodities.

Finally, I think most Christians have a deeply flawed, overly-simplistic view of God’s sovereignty to begin with. Which means that when they go to explain tragedy to doubters and cranks, they simply don’t know what they’re talking about.

I believe this pervasive and flawed view of God’s sovereignty keeps most Christians from praying as often and as effectively as God intended. And I suspect it is turning a whole generation of Postmodern young people away from God.

“So Davey,” you’re probably saying, “enlighten us. Where has most of the Church gone wrong?”

Well, this post has run on long enough. So the answer, dear reader, must wait until my next post!