Paul Harvey pulls his long overcoat around him and buttons the top button as his two companions shiver in the cold beside his car. It is nearly 1:00 a.m. on February 6, 1951, and the temperature is below freezing and dropping rapidly.

The three had rendezvoused in Chicago at midnight as planned, ridden together in Paul’s car about thirty miles southwest of the city on U.S. 66, and then pulled off the main road just before reaching the main turnoff for Lemont, Illinois. Then a series of turns on county and dirt farm roads led them into a grove of trees near a 12-foot-high security fence with three strands of barbed wire at the top. Here, within the cover of the trees Paul had killed the headlights, pulled the car off the road, and shut it off. In the distance, beyond that security fence, the men could see the lights of Argonne National Laboratory (ANL), one of the most important and sensitive installations for top secret atomic research in North America.

Now, fewer than sixty days after realizing his dream of becoming a national network news commentator, Paul is about to become national news, for within the hour he will be arrested and placed in federal custody on suspicion of espionage.

America’s respite from war and the threat of war hadn’t lasted very long. In many respects, it never came at all.

The ink was scarcely dry on the German surrender documents when General George Patton warned U.S. leaders and anyone else who would listen about the threat of Soviet expansionist ambitions. He had requested permission to use his Third Army to push the Russians out of Eastern Europe, where reports of atrocities and oppression by Stalin’s forces were already leaking out. It was clear to everyone that the Soviets had no intention of relinquishing control of any of the blood-soaked territory they had covered on their push to Berlin. And the Soviet forces were in fact weak and vulnerable, having sustained losses of more than 10 million soldiers in the Eastern Front of the war and just as many civilian deaths.

General Eisenhower and newly installed President Truman believed, probably correctly, that the war-weary American public had no stomach for a fight with a country that had been our ally only weeks earlier. Furthermore, there was still Japan to contend with.

A dizzying cascade of events seemed to validate Patton’s warning over the next five years. In March of 1946 Winston Churchill stunned a still-celebrating America by declaring the demise of freedom across half an entire continent. In a speech titled “Sinews of Peace” at little Westminster College in Missouri, Churchill had declared, “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent.” That same year a Soviet-backed insurgency in Greece triggered a civil war in an effort to overthrow the pro-Western government in that country and install a communist dictatorship.

In 1948 the Soviet Union succeeded in installing a puppet government in Czechoslovakia and a few months later triggered a crisis with its blockade of Berlin. To the latter provocation, the West had been forced to respond with the Herculean and costly “Berlin Airlift.” The following year the most populous nation on earth became “Red” China as Mao Se-tung’s communist forces drove pro-Western Chinese president Chiang Kai-shek and his armies off the mainland to the island of Taiwan.

Almost simultaneously, the Soviet Union shocked the West when it successfully tested its first atomic bomb. American military and political leaders had assumed it would take the Soviets years, perhaps decades, to replicate the technological breakthroughs achieved by the U.S. through its super-secret Manhattan Project. The speed with which the Soviets had achieved nuclear parity caused many to suspect that American secrets were being leaked from within. Time would reveal that those suspicions were correct.

Communist Party of America members Julius and Ethel (Greenglass) Rosenberg, along with Ethel’s brother David Greenglass, were instrumental in passing huge quantities of top secret U.S. military technology data to Soviet agents working inside America’s borders. Not only were key secrets about the creation of atomic weapons passed along, the Rosenbergs had also delivered the complete plans for a “proximity fuse,”—vital for the development of missile detonators— and a complete set of design and production drawings for Lockheed’s P-80 Shooting Star jet fighter.

The Rosenbergs’ betrayal of their country was uncovered in 1950, and they were tried, convicted and executed the following year. They went to the electric chair denying any involvement in espionage activity. Forty years later, however, when the collapse of the Soviet Union gave historians and reporters unprecedented access to Kremlin archives. Records from the time confirm that the Rosenbergs were indeed Soviet agents and had been instrumental in transferring nuclear-bomb-making know how to that country. Those records also reveal a labyrinth of other Soviet spying networks operating in the U.S. before, during and after the two nations became allies during World War II. These networks reached into almost every sphere of American life—corporate, academic, artistic and even the very federal government itself.

Some, like the Rosenberg ring, had been exposed. Most never were.

As if all this weren’t enough, there was one additional element about to be thrown into the stew of anxiety and mistrust simmering in the summer of 1950. In late June, communist North Korea, backed, armed and aided by Red China, invaded South Korea. The invasion presented the United Nations, formed in the aftermath of World War II, with the first real test of its “collective security” doctrine and mandate. Led and prodded by Harry Truman, the United Nations intervened on behalf of South Korea. It was almost unbelievable. Less than four years after the bloody, global war to thwart the expansionist aims of the Nazis, America found itself sending young men into harm’s way once more.

Though unreservedly anti-communist, Paul wasn’t so sure this was America’s war to fight. He was growing increasingly concerned about the security and strength of his own nation. Throughout 1945 and beyond, he had been among the voices in America urging suspicion of the Soviets and sounding warnings about clandestine Russian efforts to weaken and de-stabilize the world’s only economic, military, and nuclear superpower. Indeed it was his calm, reasoned eloquence in making the case for vigilance that had caught Joseph Kennedy’s ear and led to the broadcaster’s promotion to the network level.

Thus, when the Rosenberg spying case broke in the middle of 1950, it not only alarmed and dismayed Paul, it confirmed some of his most visceral fears and suspicions. Countering these negative emotions was the exciting knowledge that his elevation to the network was scheduled to start in a few months. He and Angel were already in discussions with the ABC Radio Network’s programming executives in New York about the what, when, and how of this new opportunity. It was an exhilarating time.

Many of the stories dominating the headlines in the opening weeks of 1951 centered around what was coming to be known as “the Cold War”—a term coined by Democratic financier and presidential advisor, Bernard Baruch. Each morning Paul’s newspaper as well as the wire service tickers he pored over would have contained numerous items about Soviet spying, communist subversion in America, and testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), testimony that grew more alarming with each passing week.

For example, on the morning of January 28, Paul would have opened his Chicago Tribune to find the following headline and article:

College Profs Tell Why They Became Reds: Secret Testimony of 2 Released by Probers

Washington—Two college professors outlined the philosophy that led to their enlistment in the communist movement in secret testimony released today by the house un-American activities committee.

Prof. David Hawkins, 37, Texas-born, now professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado, who worked during the war on the ultra-secret atom bomb project at Los Alamos, N.M. . . .

Professor Kenneth O. May, 35, Oregon-born, now associate professor of mathematics at Carleton college, Northfield, Minn, who lost his teaching position at the University of Berkeley, in 1940 because of communist activities.[i]

Even before moving his broadcast over to the network, Paul had made lax security measures at many of the nation’s sensitive research facilities a regular focus of his commentaries. There had been too many reports of breaches and compromises at civilian and university-run facilities that were doing important work for the military. When reporting one of these incidents, Paul would ask, “When are we going to start taking seriously the protecting of these secrets which are keys to our competitive advantage in the arms race and perhaps the keys to our very survival?”

One of the most important keepers of such secrets was in Paul’s backyard—Argonne National Laboratory (ANL). ANL refers to itself as “America’s first national laboratory” and with good reason. It was established in 1946 as the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory, boasted some of the top scientific minds in the country, and was a key part of the Manhattan Project team that successfully developed the first atomic bomb.

By 1950, ANL was not only the U.S. Department of Energy’s oldest research and engineering lab, it was the largest. Some of the most important and sensitive research being done there involved the creation of small, manageable nuclear reactors, the kind that will ultimately enable the creation of nuclear submarines. But Argonne did not have a spotless record where security was concerned.

On February 8, 1949, Argonne made headlines when it was reported that a bottle containing thirty-one grams of enriched uranium was discovered missing from an Argonne vault. An investigation ultimately found that all but about seven grams of the material had been shipped to Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. The remaining seven grams were found in a trash container in Argonne’s landfill. The congressional investigation that followed resulted in a tightening of Argonne’s record-keeping procedures for sensitive materials.

Sometime in late 1950 or very early 1951, amid this steady stream of reports about spying and subversion around the nation, Paul received a call from U.S. Congressman Fred Busbey (IL), a personal friend of his. Representative Busbey had someone he thought Paul would be interested in talking to. He couldn’t elaborate over the phone. Paul was intrigued and agreed to meet the man.

The mystery man turned out to be Charles Rogal, a part-time security guard and switchboard operator at ANL. He told the broadcaster a story of sloppy security, poorly followed protocols and under-qualified security staff. To Paul, it sounded like another deeply damaging espionage loss to the Soviets just waiting to happen.

Paul formulated a plan. Whether it was a foolhardy plan or not has been debated for more than five decades. Nevertheless, Paul contacted a man he knew who worked for the Office of Naval Intelligence, John Crowley, and persuaded him to join him and Charles Rogal on that trip out to the security fence in those early morning hours of February 6.

* * * * *

As his two companions watched, Paul began to scale the fence. When he reached the top, however, his overcoat snagged on the barbed wire. He struggled for several minutes to pull free, and before he could get clear, a jeep patrolling the perimeter happened by.

When his companions saw the headlights approaching they slipped off behind some bushes and then ran off through the trees. They eventually came to the main road and caught a ride back to town. Unfortunately for them, they left a wallet and some identifying papers behind in the car.

The following day, puzzled Tribune readers learned of this improbable event:

Paul Harvey Seized Inside Atom Lab Area

Paul H. Aurandt, 3400 Lake Shore Dr., an American Broadcasting Company radio and television newscaster under the name of Paul Harvey, was seized by a guard at the Argonne National Laboratory in Du Page county at 1:10 a.m. yesterday, a few minutes after he had climbed a fence surrounding the laboratory’s restricted area.

News of the arrest was released in a statement by the atomic energy commission only after it was approved “at the highest level” in Washington. Aurandt was turned over to Federal Bureau of Investigation agents for questioning and later released.

Later in the day Aurandt said: “I have been working in conjunction and cooperation with the investigating divisions of several departments of the United States government for the last several months. I am not at liberty nor am I authorized by the governmental investigating divisions to release any story or information concerning the matters upon which I have been working.”[ii]

Follow-up stories appeared in papers across the country for several days thereafter, with much speculation about what government agencies, if any, Paul may have been working with to test ANL’s security measures. Few in the general public or the press seemed inclined to believe that Paul Harvey was a Soviet spy. Federal investigators on the other hand weren’t so sure. Records indicate they didn’t know what to make of the incident.

Everyone had an opinion about it, though. University of Chicago professor and researcher, Dr. Harold Urey, winner of the 1934 Nobel Prize in chemistry, was quoted as saying he was disappointed that guards did not shoot Harvey. When reporters asked accomplice Charles Rogal—who was fired by Argonne after the incident— if there had been any fear of being shot by guards, he said, “Not one of them could shoot and hit the side of a barn.”[iii]

There was much mirth and joking surrounding the whole thing, but it didn’t change the fact that Paul was potentially in serious trouble. The federal government was planning to bring charges that carried a possible 10-year prison term and $10,000 in fines.

A federal grand jury was called. Presiding was a future Illinois governor, U.S. Attorney Otto Kerner. He heard the charges against Paul: “conspiracy to obtain information on national security and transmit it to the public.” In response, the broadcaster requested permission from Kerner to appear before the grand jury. Kerner agreed on one condition: Paul had to first sign a waiver of the right to later claim immunity from prosecution for anything his testimony might reveal.

The accused happily signed it. The professional talker apparently had a high degree of confidence that if he could get the ear of the grand jury, they would view his act as more of a public service than a crime. His appearance was scheduled for March 21.

In the interim, the feds view of Paul apparently softened considerably. The Chicago office of the FBI even filed a supplemental report, indicating that, upon further study, the Justice Department had reached the conclusion “that Aurandt had not willfully violated security laws.” Paul also received a good word from an unexpected source. As the Tribune reported, “Merlin W. Griffith, business agent of the Argonne security guards union, yesterday praised Aurandt for exposing what Griffith charged were security ‘flaws’ at Argonne.”[iv]

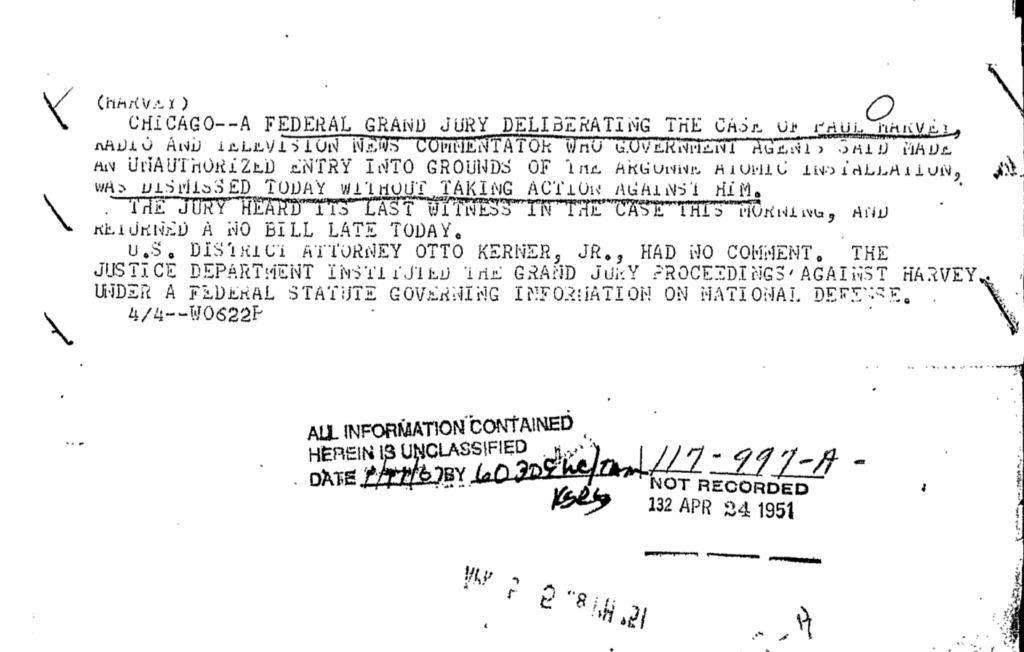

Paul’s confidence turned out to be well founded and his appearance must have had its desired effect. On April 4, 1951, the grand jury voted not to indict him. Later the foreman of the grand jury told the press the vote was not even close.

Precisely what Paul was thinking when he climbed the fence that night remains a matter of debate. It was something that, in his later years, he declined to talk about. It seems most improbable that he was working officially on behalf of any government agency. If a high-level department wanted to see if Argonne’s perimeter could be breached, they would almost certainly not recruit a radio newsman in a wool overcoat for the task.

Perhaps a savvy self-marketer who had just gotten himself a national newscast thought it would be a brilliant promotional ploy to breach one of the country’s most sensitive facilities. The headlines would really put him on the map. But this motivation seems deeply out of character with everything else we know about the life and values of Paul Harvey. The most plausible explanation is the most obvious one.

What he learned from Charles Rogal about the security situation at Argonne must have troubled him profoundly. In the wake of the ongoing Rosenberg affair, he was concerned that secrets and technologies vital to the safety and survival of our nation were at risk. He and others had been publicly calling for greater vigilance for several years but without apparent effect. So he took it upon himself to expose the vulnerability the only way he knew how.

It would be like a volunteer fireman setting a small blaze to create a fire break, in hopes of keeping an inferno from destroying his town. The fact that this would-be firefighter could easily have gotten himself shot either didn’t occur to him or didn’t matter.What was clear to Paul in early 1951 was that communism was spreading like a prairie fire in a drought all over the world and that, inexplicably . . . maddeningly . . . a good number of the brightest, most talented and most privileged of his fellow Americans considered this a good thing. Even more bewildering to him was the desire of some of them to bring that fire to our shores.

[i] Edwards, Willard. “College Profs Tell Why They Became Reds.” Chicago Daily Tribune 28 Jan. 1951: p. 32.

[ii] “Paul Harvey Seized Inside Atom Lab Area.” Chicago Daily Tribune 7 Feb. 1951: 8.

[iii] McGregor, Steve. “Argonne passes a reporter’s security test.” Argonne National Laboratory. p. 6 Feb. 1996. 21 Mar. 2009 <http://www.anl.gov/Media_Center/News/History/news960206.html>.

[iv] “Kerner to Read FBI’s Report on Harvey Seizure.” Chicago Daily Tribune 13 Feb. 1951: p. 8.