Originally posted on BWR, March 2010

Female Offspring Unit #3 and I drove down to Austin Friday night so she could participate in a thingy Saturday morning. By Saturday afternoon we were headed back up I-35 toward home.

Now I have always endeavored to bring up children who are culturally literate and appreciators of fine art. That’s why I’ve insisted each of them have a broad knowledge of late 70s classic rock, disco, and early 80s New Wave.

Why allow a teenager to remain isolated in an iPod, Jonas Brothers cocoon when she can be introduced to the stark differences in Doobie Brothers music pre-and post-Michael McDonald?

On this trip, we discussed one of my favorite topics–“Misheard Lyrics.” Misheard lyrics are words to a song that are sung in such a mumblypeg way that you have no idea what’s actually being sung, so your mind makes something up–even if it makes no sense.

The trigger for this discussion was hearing Fleetwood Mac’s song, Dreams. It’s a long-standing joke between me and FOU#3 that Stevie Nicks is singing this lyric:

Women, they will come and they will go.

When Lorraine watches you clean your nose.

Stevie Nicks is the queen of misheard lyrics. The titular hook in Nicks’ duet with Tom Petty is Stop Dragging My Heart Around. But millions thought they heard, “Stop driving my car around.”

In her duet with Don Henley she sang, “Give to me your leather, take from me my lace.” But many heard something else. Among the interpretations of Nicks’ utterance in tongues was:

Give to me your liver. Take from my, my legs.

Give to me your letter. . . J. Cromley’s my name.

Give to me your ladder . . . J. Cromley, my ace.

The band Boston and Elton John have also proved an enduring source of lyrical confusion. The line from Boston’s iconic song, More Than a Feeling: “I see my Marianne, walking away,” has bewildered several generations of radio listeners. It has been sung:

I see Maid Marion, walking away.

I see my derriere walking away.

And thousands of other delicious iterations.

One of the most famous misheard lyrics of all time is a line from Jimi Hendrix’ “Purple Haze”. An astonishing number of people through the years thought the line “‘scuse me, while I kiss the sky,” was actally:

‘scuse me, while I kiss this guy.

Perhaps that’s because they were in some sort of lavender fog themselves.

“Kiss this Guy” is the name of a website devoted entirely to misheard lyrics and it makes for pretty hilarious browsing. But I digress. Back to our road trip . . .

A Detour Down “Roots 66”

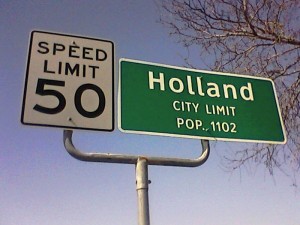

As we approached Temple, Texas from the south we reached the exit for Holland, Texas. I’ve driven past the sign scores of times and told myself that someday . . . on a day when I wasn’t in such a hurry to get where I’m going . . . I was going to take that exit and visit Holland. This was that day.

As we drive the nine miles off the Interstate toward Holland, I told my daughter the story of how it got its start in 1874 when my great-great-uncle James Holland bought some land and moved there from Tennessee by way of Arkansas. He had cotton farming in mind.

Shortly thereafter he was joined by his father (my ggg-grandfather John A. Holland) and seven siblings. There, in those post-Civil War years, they homesteaded on Darr’s Creek and built the first steam-power cotton gin the area had ever seen.

Some of the houses from the 1880s are still standing in the area.

In the decades that followed, Holland seeds blew all over Bell county, taking root in tiny towns with evocative Texas names like Cyclone, Prairie Dell, Red Ranger, and Salado.

Today, you’ll find the graves of John A. and Louisa Holland, side by side, at Cedar Valley Cemetery outside of Salado. John’s headstone reads:

Born June 19, 1824 – Died May 7, 1908

My daughter and I talked about all of the boisterous history that is surely squeezed into that delicate little dash mark sitting quietly between those dates. Eighty-four years of sweat and heartache and adventure and accomplishment.

As a boy, he would have seen men who served with Washington in the Continental Army. Before he died, he would read of the Wright Brothers motorized flight at Kitty Hawk and see babies who would be alive for the birth of the Internet and the dawn of the 21st Century.

I would have loved to have heard his stories, but I was born about 60 years too late. He might have carried some anecdotes from his own grandfather, who had ended up in the mountains of East Tennessee (Grainger County) by way of a land grant he earned fighting the British in the War of 1812.

Shortly after the turn of the 20th century, my great-grandfather, Samuel Houston Holland, born in 1884, left Bell County, Texas for Sallisaw, Oklahoma. The motivation for his move is not known to me–but it’s the reason I and hundreds other Hollands were born in the Sooner state rather than the Lone Star Republic.

He’s this tall glass of charged water:

He had 11 children. One of them, my grandfather, died when I was two. So even his stories are lost to me.

As #3 and I, drove north out of Holland on Texas 95 — past river-bottom land featuring tidy, evenly spaced rows of 120-year old pecan trees probably planted by her ancestors or their friends — I made myself a promise.

She and her sisters will know my stories. They already know my music.