The series Mad Men ended the other night after a celebrated eight-year, seven-season run. The show was consistently brilliant in many respects. Amazingly executed, written and performed. But I was a little slow on the uptake where the series was concerned—in more ways than one.

For one thing, I didn’t start watching until midway through the second season. I was hearing lots of buzz so I checked it out, and was immediately drawn in on two fronts. The first was the show’s meticulous . . . make that maniacal . . . recreation of the early ’60s in every detail. I was born in 1959, so my earliest memories are of that era.

Long-time readers will know that I have a soft spot for Mid-Century ephemera and design. (A glance at all the headers from my old blog will confirm this.) (As will the vintage 1964 Omega Seamaster watch I’m wearing as I type these words.)

So at first I enjoyed watching just to bathe in details of each set. For me, and many other loyal viewers, nostalgia was a big attraction. Behold . . . Mid-Century Modern awesomness . . .

The second attraction for me was the window the show offered into the inner workings of a NYC ad agency. As a child, my favorite episodes of Bewitched were the ones that showed Darren Stevens in his role as an ad man at the firm of McMann & Tate. Anytime an episode featured Darren working on a new campaign or trying to come up with a new slogan, I was fascinated.

In fact, I recall thinking that Darren Stevens’ job was precisely what I wanted to do when I grew up. And in a strange way, that’s what happened.

It was only after watching Mad Men for a few seasons and then going back to watch the series from the very first episode that the worldview and agenda of the show—created and guided by Michael Weiner—became abundantly clear to me. (As I mentioned, I was a little slow to catch on.)

A simplified summation of the show’s theme and message is this:

“Men are pigs.”

Or to be more precise, “Straight, white men are pigs—at least they all were back in the day . . . before the noble cultural revolutions of the ’60 overturned the oppressive order and put us on the path to cultural enlightenment.”

That’s the pervasive, overarching, unfolding narrative of Mad Men. And all one really has to do to see this is the case is merely watch the very first and last episodes of the series back to back.

The pilot is set in in March of 1960. The events of the final episode occur in November of 1970. They bookend a decade of extraordinary cultural, moral and technological change.

In the pilot episode, Don Draper is introduced to us as a hard-drinking, chain-smoking, philandering, anti-Semitic, arrogant cad.

In the pilot episode, Don Draper is introduced to us as a hard-drinking, chain-smoking, philandering, anti-Semitic, arrogant cad.

Roger Sterling: Hey have we hired any Jews here?

Don Draper: Not on my watch.

But we soon discover Don is actually one of the more sympathetic men in Weiner’s caricature world. Indeed, every other male we encounter in this fictional universe (with two significant exceptions) are the most horrible and horrifying human beings you’ve ever observed.

Every single scene of the first episode is a freak show of misogyny, racism, entitlement, crudity, rude-ity, and cringe-inducing frat-boy boorishness.

Every woman in the pilot is always and only running a harrowing gauntlet of sexual harassment punctuated by insulting condescension. Some, like the va-va-voomy head secretary Joan, have learned to enjoy the attention. But most just try to put on a brave face and periodically retreat to the bathroom to sob.

I mentioned there were two exceptions to the “men are monsters” theme of the first episode (and indeed the entire series.) They were the closeted, repressed homosexual art director, Salvatore; and the frustrated novelist copywriter, Paul—a marxist intellectual (who in the first few episodes seems to be the only white person on earth who can actually see the black elevator operator.)

I mentioned there were two exceptions to the “men are monsters” theme of the first episode (and indeed the entire series.) They were the closeted, repressed homosexual art director, Salvatore; and the frustrated novelist copywriter, Paul—a marxist intellectual (who in the first few episodes seems to be the only white person on earth who can actually see the black elevator operator.)

Other than these, there are no male characters with even a shred of decency—much less nobility. None. It’s bad husbands, bad fathers and bad bosses as far as the eye can see.

In other words, Matthew Weiner’s Mad Men was viciously, relentlessly anti-male.

Validating Liberal Mythology: Redeeming the Sick ’60s

Conservatives tend to believe that our nation lost it’s way in the 1960s. That the drug culture; the sexual revolution; the rejection of traditional sex roles; the abandonment of marriage and family as the organizing paradigm of society; and the embrace of Marxist-Socialist premises about how the world works economically; set our nation on a disastrous course.

Conservatives tend to believe that our nation lost it’s way in the 1960s. That the drug culture; the sexual revolution; the rejection of traditional sex roles; the abandonment of marriage and family as the organizing paradigm of society; and the embrace of Marxist-Socialist premises about how the world works economically; set our nation on a disastrous course.

One from which we’ve never recovered.

Liberals like to believe the opposite–but point almost exclusively to the Civil Rights Movement to make their case. The argument over the 60s usually goes something like this:

Conservative: “Fatherless-ness in this country is a heartbreaking tragedy—creating widespread poverty, crime and imprisonment rates. Back in the 50s most kids got to grow up on a two-parent family and our society was much better for it.”

Liberal: “Oh, so you want to go back to the ‘good old days’ of separate water fountains for blacks and whites, eh, Hitler? You probably have a Klan hood hidden in your sock drawer.”

Conservative: “Um, no. It’s just that a lot of the key supports under-girding our civilization were deliberately knocked out in the 60s.”

Liberal: “You mean like the Jim Crow laws? Why do you hate black people?”

Conservative: “That’s not at all what I’m . . . oh, nevermind.”

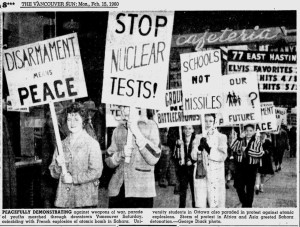

It’s true that conservatives were largely wrong about the civil rights movement, mainly because they couldn’t find a way to separate it from the larger cultural battle taking place over traditional values; or from the Cold War paradigm (the threat of the Soviet driven spread of global Marxist-socialism) that permeated every other aspect of life in the ’60s.

In other words, the civil rights movement was presented to most Americans as only one element in a  larger bundle of societal changes being relentlessly pushed by Progressives. That bundle included rejection of capitalism in favor of Marxist redistribution of wealth and the rejection of the notion of private property.

larger bundle of societal changes being relentlessly pushed by Progressives. That bundle included rejection of capitalism in favor of Marxist redistribution of wealth and the rejection of the notion of private property.

It is no coincidence that Lyndon Johnson’s Civil Rights Act of 1964 and his “War on Poverty” legislation were presented simultaneously and as two halves of a whole.

The former was noble and necessary. The latter was arguably the worst thing to happen to black people since the first Portuguese slave ships showed up off the west coast of Africa.

In retrospect, conservatives were wrong to oppose the first and absolutely correct in opposing the second. Unfortunately, the two were inseparable.

If you read conservative essays from the ’60s you’ll find lots of hand-wringing about whether or not civil rights leaders were being influenced or financed by Soviet front groups. These fears may seem comical now, but the concerns were very real at the time. And, as we learned after the collapse of the Soviet Union made lots of Kremlin records available to researchers—the Soviets were indeed actively encouraging, not to mention financing, a lot of Progressive groups and campus rabble rousers—and had been for decades.

Many of these ended up running the country in the ’90s and beyond . . .

So the dispassionate verdict of history is that conservatives were wrong about the Civil Rights Movement and right about everything else. But liberals don’t like that verdict. So, on to . . .

Validating Liberal Mythology: Redeeming the Dreadful ’60s

In response, Matthew Weiner seems to have written Mad Men as an attempt to redeem the cultural upheavals of late ’60s by painting the world of the early ’60s in the darkest possible shades.

- He refutes critiques of the sexual revolution by depicting virtually every person in the Mad Men world as being sexually amoral and in constant violation of their marriage vows.

- He negates condemnation of the drug culture by making every character a high-functioning alcoholic and chain smoker.

- He attacks negative perceptions of the feminist movement, as I mentioned above, by creating a world in which every straight white man is insulting, selfish, abusive, harassing, and belittling to women.

In other words, it’s the typical Progressive argument. That is, the ’60s didn’t really represent a change in behaviors. It just made all the depravity less hypocritical by moving it out in the open.

By Eastern New Age Group Therapy Are Ye Saved

The most disappointing (but given everything I’ve already cited, not all that surprising) aspect of the way the series ended (spoiler alert) is having Don Draper—hitting rock bottom— find peace and enlightenment at a New Age-y group therapy retreat camp on the California coast.

Observers have noted that the place Don lands is surely modeled on a place called the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California. The place was ground zero for something in the sixties called the “Human Potential Movement.”

In the final episode Don stumbles into the place and ends up in a series of group therapy sessions in which the participants are incessantly asked about their feelings. “How does that make you feel?” has become a jokey cliche associated with quack psychiatry, but in these groups this is taken to absurd levels.

“Carl, how does that make you feel?”

“And John, how do you feel about how that makes him feel?”

And so on.

That’s right. Mad Men ends with America’s most iconic selfish rogue being transformed into a touchy-feely new age sensitive guy through the power of meditation, hugging and hippie love.

Ask my wife . . . As this became clear the first time I viewed the finale, I started yelling at the television:

“Are you serious?! You’ve got to be kidding me!”

I haven’t been as let down by a series finale since LOST wrapped up.

But there was one aspect of the transformations that occurred in the sixties that Weiner & Co. couldn’t conceal—not and still remain true to their fanatical devotion to recreating the period’s look and feel. I’m talking about how hideously ugly everything got as the decade of the sixties progressed.

Plaid Men

What this series makes massively clear is that in one short decade this culture lost its collective mind where design and aesthetics are concerned. Everything—architecture, clothing, art, typography—went to hell.

What this series makes massively clear is that in one short decade this culture lost its collective mind where design and aesthetics are concerned. Everything—architecture, clothing, art, typography—went to hell.

We started with the clean, classy Mid-Century furnishings that are so prized today. Here’s Roger Sterling’s office in 1960:

Here’s Roger’s office nine years later . . .

In which space would you rather spend your days?

Those two pictures pretty much tell you everything you need to know about the the sixties—the decade the wheels came off.